Realized today I am doing things in Polish that before were a big deal, to wit: texting in Polish and understanding when a clerk in a store or restaurant tells me how much something is. (I know that sounds crazy to those of you whose only foreign language experience is French or Spanish or Hebrew or English or Italian or German (or, or, or) but numbers in Polish change depending on the case, plus the words for nine and ten are so similar that I have had trouble understanding the exact amount that’s owed when I am buying something. Now I seem to understand the, for example, 47 groszy part of the purchase). Another thing is I am understanding when someone makes an aside to me—instead of ignoring it and just assuming it’s meant for someone else because it’s in Polish!

A Visit to Parczew

Kirkut or Jewish cemetery in Parczew. Now a park.

Former mikveh, Parczew.

Former Great Synagogue, Parczew.

Today, as part of the Mary Elvira Stevens Traveling Fellowship from Wellesley College I went to my ancestral town of Parczew. My friend Witek has a friend, Jarek, who is the principal of a school there and he had arranged for a get together. We arrived and he showed me student books from the 1930s with names and grades of students. Witek had told Jarek in advance that my great, great-great and great-great grandfathers had been born in Parczew and had been named Bawnik (my great-great-great grandfather was born there too but he was born in 1800 when they still used patronymics—no last names). So in advance someone had looked through all these books and marked the pages that had the name Bawnik on them. Funnily enough Bawnik was often next to Banach. I have written elsewhere about my friend, the historian Krzystof Banach, formerly of Majdanek with whom I have a shared history: both his great grandfather and my great uncle were murdered in Majdanek. And now in these school ledgers that are nearly ninety years old I find the names Banach and Bawnik side by side. Jews and Catholics studied together in this school; over and over again I see the words Roman Catholic and Mosaic listed as the children’s religion. The pre-War Jewish population of Parczew was 60%. My direct relatives left there in the 19th century but the two Bawniks whose grades I saw today—Mindla and Józek— are likely relatives of mine.

After looking at the books we head into a large classroom for a gathering. Students recite poems about Parcew Jews and we see some photos and a film about Parczew before and during the War. Witek gives an introduction and then I give a spiel in Polish. Of course I make a lot of mistakes but I am getting more and more comfortable speaking, and moreover, understanding in Polish. One woman asks me what American Jews think of Poles and I tell her that there are many different opinions among American Jews— many don’t think about Poland, some are interested and supportive, but unfortunately there are some who are quite anti-Polish. I tell her that I believe this anti-Polish sentiment stems mostly from pain and that pain turns to anger and they need somewhere to put the anger. I say that one of my missions in life is to combat anti-Polish sentiment. I wasn’t planning to say that but I am glad I got the opportunity. Later, my friend and mentor, Tomek Pietrasiewicz points out that for the people in the room who heard me say that, it is likely a breaking of stereotypes that a Jewish woman would say such a thing.

After eating a delicious gluten free lunch (except for a suspicious grain that I left on my plate) —kids in Poland eat really well—Witek, Jarek, a knowledgable guy named Stanisław and I go to see some parts of Parczew related to the Jews:

1). Kirkut, or Jewish Cemetery. Basically it’s a park. There are no tombstones. No one knows where any of them are. There’s no plaque saying what the place was. There was one but it was stolen. Stanisław tells us that everyone know this space was the Kirkut. I asked, “everyone?” He said that the old people definitely do, maybe the young don’t. So I wonder: what will happen to the memory in the future?

There are a few monuments in the park and one of them’s a grave. Though I read Hebrew I could not make it out. Another is a plaque dedicated to the Polish Jewish soldiers who were murdered there. And Stanisław says there were several mass graves on the area of the Kirkut.

2). Former great synagogue. Nothing remains except the outside of the building.

3). Former smaller synagogue. An empty grassy lot. They don’t stop long enough for me to snap a photo. I asked why it is empty, assuming it is for some reverential reason, but Stanisław said the owner just does not want to build on it.

4). Former mikveh. Just the building remains.

5). Stanisław and Jarek know where the ghetto boundary was. In Lublin, thanks to Tomek Pietrasiewicz, the ghetto boundary is marked with yellow squares in the pavement. You cannot help but remember. I wonder how many remember those boundaries in Parczew.

6). The last standing “Jewish house” in Parczew.

Last standing Jewish house according to our hosts. Parczew.

Fat Thursday

It’s Fat Thursday in Poland and people line up to buy pączki or jelly doughnuts.

No translation Needed (Sometimes)!

The other night I went to a meeting of representatives of various NGOs trying to figure out how they could form a coalition. I got the general gist. I even said who I was and what I was doing in Poland in Polish when the circle came around to me but it was really hard to follow what was going on and I felt quite discouraged.

Enter the next day—a new dawn—when I was interviewing the mayor of Central Warsaw, Krzysztof Czubaszek, who in his spare time commemorates the Jews of his hometown of Łuków. Considering how much amazing stuff he has done you’d think he had tons of spare time! Besides being blown away by the depth and breadth of his work and the strength of his commitment I was impressed (with myself!) that though I had a professional translator there I often did not need him and understood what Krzysztof was saying. How cool is that? So, it seems context is everything.

Krzysztof Czubaszek, Mayor of Central Warsaw and Rescuer of Memory of Łuków Jews

Memorial to the Jews of Łuków who were murdered by the Germans, one of Krzysztof’s many initiatives.

What's in A Name?

My kids kid me because I have so many friends and acquaintances named Andy or Andrew. Lately they are being replaced by Annas, Agnieszkas and Krzysztofs. And I been connected with at least three new Zbigniews in the last month. Go figure.

GGGG

Thanks to Tadeusz Przystojecki, genealogist extraordinaire for all descendants of Lublin Jews, I have discovered that I have Lublin roots going back into the 1700s! My great-great-great-great grandmother Roza Jenta was born in 1789 in Lublin! So way back when Marie Antoinette was letting them eat cake, my family was already in Lublin. Amazing and pretty cool. Roza Jenta’s parents were Ruchla and Icko but I don’t know were they were born. Roza Jenta’s husband, Szymon Bornstajn was born in the picturesque town of Kazimierz Dolny where they made many films including the Molly Picon classic, “Yidn Mitn Fidl.” Szymon (pronounced Shimon) was by profession a spekulant małe stopy, which though literally means a small foot speculator I suppose means he did small scale business deals. In any case my Polish friends cracked up when they heard this profession and deemed it even funnier than my great-great grandfather Binem’s. He was a leech seller! Gotta love the rellies.

Tea Themes

Lipton is helping me to practice Polish. Certain boxes of tea have conversation starters on each teabag.

Enabling Me to See

One of the best metaphors for my relationships with my Polish friends, particularly those at Brama Grodzka-Teatr NN, is that they shed light on things for me. Here is a literal example. My friend Emil Majuk is lighting up the indentation where a mezuzah used to be in a doorway in Międzyrzec Podlaski, the town where my great-grandparents Syma and Hersz Pejsach Finkielsztajn and their daughter Zelda lived.

February 1, 2019

International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Poland, 2019

Thank you, my friends, at Brama Grodzka, from the bottom of my heart, thank you.

A Day, A Year of Mourning

Me and my father (born 1919)

January 19. I don’t usually think about the day my father died even though it is Jewish tradition to do so. I prefer to think of him on his birthday. This year January 19 is a national day of mourning in Poland in memory of Paweł Adamowicz, the mayor of Gdańsk, who was stabbed to death last week. It’s the 6th anniversary of my father’s death. 2019 is also the year my father would have turned 100, so he’s been on my mind more than usual.

My grandmother’s youngest sister Zelda was born in 1919 as well. I know little about her. From my mother’s memoir, “Dry Tears,” I know that she had red hair and was unmarried, and her parents thought her too choosey when it came to men. My great-grandparents were worried she would never get married. She never did. The Germans murdered her before she had a chance.

A few years ago when reading my aunt’s memoir in Hebrew, “Skating on Thin Ice,” I learned that Zelda sang and played the guitar beautifully. Learning this seventy-five years after her death was a small gift–a piece of her that came back to me. I thought I would never learn anything else but then it happened again. In my latest reading of “Dry Tears,” which I have read many times, I paid attention to something I had not noticed before. My grandmother saw her sister being taken away in a truck, and ran after it in vain, only to see Zelda reach out and beg her to help in some way. Of course my grandmother could do nothing and was devastated. Perhaps because I had felt her devastation I had not taken in what followed in the book, which was that my endlessly resourceful grandfather found out what happened next. Zelda had been taken away and put on a train bound for a camp, she had jumped off that train and was hiding with non-Jewish Poles in the countryside. To me it’s amazing that Saba Roman (my grandfather) was able to discover so much detail. Not only that, but he was able to get word to Zelda that she was invited to join them. She refused however, believing that she would have a better chance of survival where she was.

My mother, her parents and her sister were one of three nuclear families out of Lublin’s 43,000 Jews to survive the Holocaust intact. None of my grandmother’s siblings or their children survived. And of my grandfather’s siblings and their children only his brother Gerszon made it. Who knows if Zelda would have survived if she had come to join her sister’s family. Would adding another person to the group have placed them in danger? Would she have been able to pass? Did she know Polish fluently like her brother, or did she speak it poorly like my grandmother? We will ever know. If she had survived I could have easily known her. As I said, she was the same age as my father. For that matter I could have known my great-grandparents Syma and Hersz Pejsach Finkielsztajn, who were both born less than 90 years before me—Syma, less than 80 years before me. But that was not to be. The only people who survived from my mother’s closest family were her parents, her sister and her uncle. (For info on my newly discovered cousins in Poland see an earlier blog post—a cousin did survive).

When I was little my mother used to light a candle on the day of her father’s death. That was the only person she lit a candle for. Most Lublin Jews were murdered in 1942. Most in the span of three months, but we don’t know the particular days that each of our relatives died. When should we light the candles for Golde, her husband and her four boys; for Chana, her husband and her children including Avigail; for Icek, Topche and their children: Chanina Dow, Nechemiasz Dawid and Henek; for Zelda; for Elka, her husband Shmuel and their children; for Cyla and Eljusz; for Syma and Pejsach and for all the other cousins and their children?

My grandmother’s sister Zelda was also born in 1919, but we have no photo of her.

A New Way in to "Dry Tears"

I am lucky, thanks to the Fellowship Committee at Wellesley College to be spending several months in Poland as a Mary Elvira Stevens Traveling Fellow doing several projects related to Jewish memory. I am doubly lucky to be partnering with my friends at Brama Grodzka-Teatr NN, the cultural institution and theatre in Lublin devoted to Jewish memory that inspired me to start Bridge To Poland. Brama Grodzka is a municipally funded institution staffed entirely by non-Jews. It has been inspiring these last few months to actually have a desk at Brama and to come here every day. I have started giving tours, I have met with Polish schoolchildren and told them (in Polish!) about my family connection to Lublin; I lit Hanukah candles for them. I have interviewed rescuers of memory for a video archive I am building on the Brama website, and I have uncovered information about my family’s past.

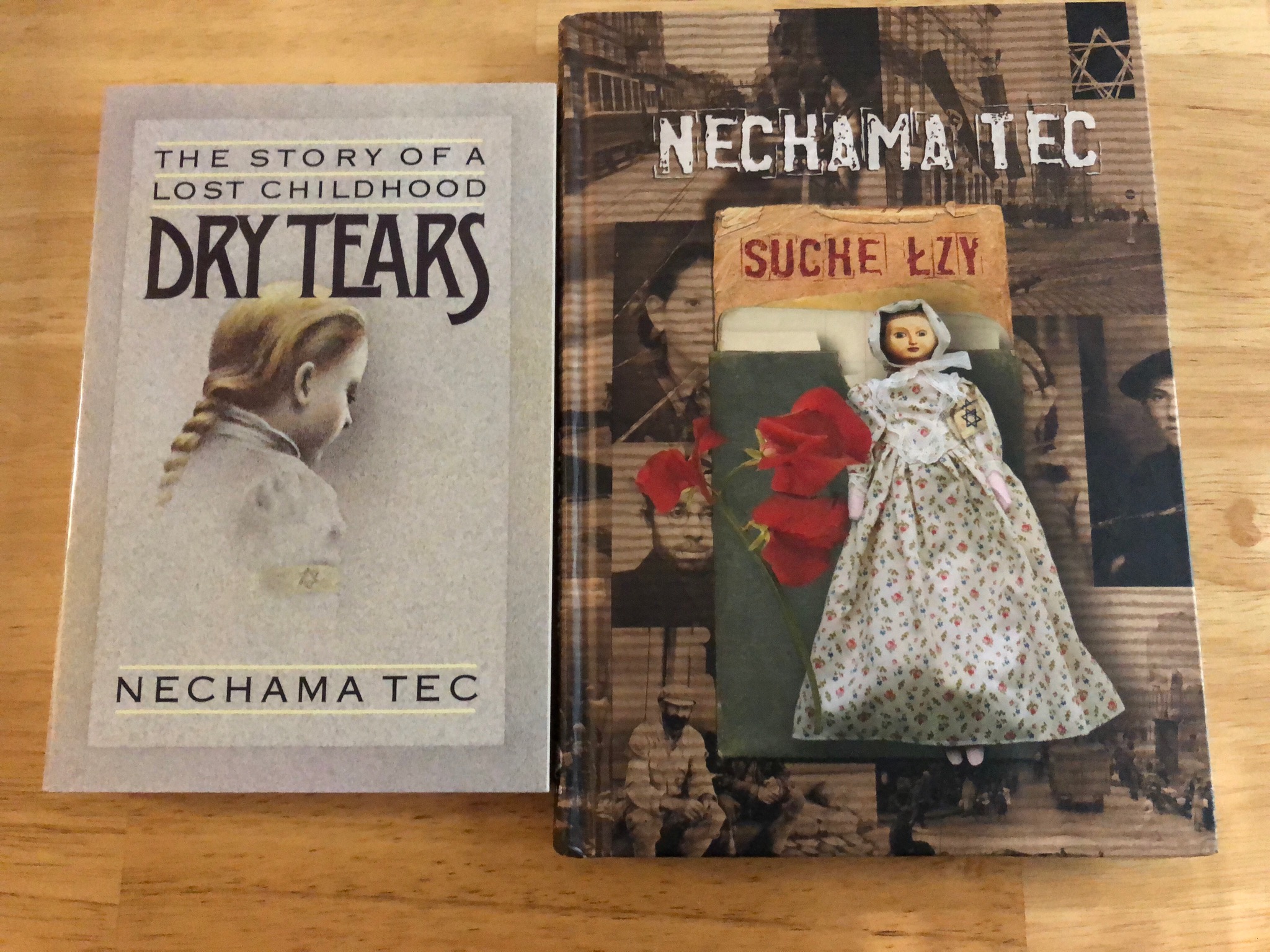

A couple of weeks ago I started teaching a class based on my mother’s memoir of surviving the Holocaust while passing as a Catholic girl, “Dry Tears.” As very few Lublin Jews survived, and even fewer, of course, wrote their stories down, this account is of particular interested to the folks at Brama who consider their institution an Ark of Memory.

“Dry Tears” by Nechama Tec (aka my mom) in English and Polish

When practicing for the first class in the privacy of my apartment I got choked up as I told my imaginary pupils that I was touched and honored that they wanted to take the class. The pretense for the class is to learn English but it seems most of them are there more for the content. They want to know the story and they want to know my second-generation take on it. I feel moved to tears by this interest (even as I type this in a café, I am holding back the tears).

What’s been amazing about this class is because the participants are so steeped in this history, they are offering me new perspectives, “Have you ever thought your mother could have played with Henio Zytomirski in Majdan Tatarski?” D. asked the other day. (Henio was a boy born two years after my mother who is part of the exhibition at Brama Grodzka and about whom a workshop called “Letters To Henio” is conducted. His father took a photograph of him every year and sent those photographs to their cousins in Israel. See my article: https://medium.com/@lavcloud/a-photo-waiting-to-be-seen-803636d94425). Other people got excited about mapping out the locations where my mother’s family lived and where my grandfather’s factories were. They tried to figure out the streets based on clues, “If your mother looked out at a convent from the factory, it couldn’t have been at this location.” What a gift to be able to re-read the book with this panel of experts!

We all know the survivors will soon not be with us. And sadly we, the children of survivors, will be the next to go. Parallel to us are those people of my age, like my deep, soul friends Tomek and Witek, the heads of Brama Grodzka, who inspire me over and over again with their dedication to remembrance. When we are gone we will need these younger people to keep on telling the stories in a faithful way. I’m so grateful that they care.

Tomek, Me, Witek, when we were the young ones! (2007)

The Mayor of Gdansk is Dead

The Mayor of Gdansk was stabbed to death at a charity event. He was a liberal. He was a father of two. Poles are stunned. It reminded me of when Itzchak Rabin was murdered right down the street from where we lived in Tel Aviv. One of my friends said it was like JFK. RIP Paweł Adamowicz

"Different" Things About Poland

I’ve been in Poland for a couple of months and though for the most part I love it, there are some little things that are different from back home*:

They have great peanuts and bad peanut butter.

I don’t understand this. The peanuts are very good—great flavor. Can they just crush them and get great peanut butter? I miss Teddie Peanut Butter.

At salons they use paper towels to dry your hair.

This has happened to me in two different salons. I suppose it’s because keeping up with laundry is tough but this is both weird and bad for the environment. There doesn’t seem to be much awareness about stuff that’s bad for the environment though.

At salons they seem annoyed when you walk in to make an appointment.

This has also happened to me twice (coincidentally—perhaps, perhaps not, at the two salons that used paper towel to dry my hair). I walked in to make an appointment because it’s easier for me to communicate in Polish face to face when I can flail my arms around and look into the listeners eyes to search for a glimmer of understanding. In both places the stylist was working on someone’s hair and looked surprised (in one case mildly annoyed) that I had walked in to make an appointment (receptionist anyone? I understand that would be an added expense but if there isn’t one then at least be courteous when potential clients drop in).

They really, really like exact change.

Numbers in Polish are really hard. Because of the cases there are all these crazy (ok, that’s a subjective opinion but I’m not the only one who holds it) rules. Like it feels like there are a million ways to say “two” depending on various things. So going to a store and understanding what I am supposed to pay the cashier is tough if the number is not displayed on a screen. The situation takes on an added layer of stress when, as happens quite often in Poland, you hand the sales person a bill, say for twenty złoty when the bill came to 17.30 PLN and she says, “Does Madame (my English approximation of the Polish Pani) have by any chance two zloty and 30 groszy?” when I am still trying to make sure I understood 17.30 correctly.

The coffee is almost never hot enough.

This is true even if I ask for it to be very, very hot. I don’t know what’s up with this but it’s annoying. (Oh, and it goes without saying—well, maybe not because I am saying it—that it’s much harder in general to find decaf than in the States).

They don’t sand or salt the sidewalks enough (see attached photo).

It’s very cold here. And snowy. So it’s not like they don’t need to sand and salt the streets and sidewalks. I think it must be a question of budget and the fact that it’s a much less litigious society than ours. My Polish teacher’s mother slipped and broke her wrist the other day. She is certainly not thinking of suing anyone. It took me double the amount of time to walk to work this morning because I was so afraid of slipping and falling. Other colleagues had the same experience. One of them did fall.

Some people feel they get too much vacation.

One guy I know was bummed because he had to take “forced vacation.” Another came back from vacation and I asked him how it was and he started saying, “Too—” and I was sure it was going to end with “short,” but he surprised me and said, “long!” “Too long?!” I exclaimed, “In America everyone complains that it’s too short.” “Yes, he said, but you only get two weeks, we get 26 days.”

Sometimes people won’t take a tip.

This happened in one of the hair salons. In the other (which was double the price) she happily took the tip.

It’s really gray here.

Those of you who have heard me speak or read my writing about how people often assume that Poland is a gray or black and white country will laugh at this tidbit ,but the thing is I have never spent an entire winter here. At home I probably wear my sunglasses as much in the winter as in the summer. Here after the first couple of weeks I have not worn them at all. I could never relate to S.A.D. (seasonal affective disorder) before, but now I see why people get depressed without sunlight.

*I am reporting on my experience and things will surely be different in different places and for other people.

The steps leading down to Pilates class.

The steps leading down to Plac Zamkowy or Castle Square (once the main Jewish part of Lublin, now erased). Many people, including many old people, go up and down these stairs every day. On the day I took this photo it was 16 degrees Fahrenheit out.

Polish Language Learning Continued

Continuing with the Polish studies. I’m in this frustrating place where I feel like I am on a plateau, I feel people have no patience for my less than perfect (to be generous) Polish, I can’t be me in Polish, I feel lazy to speak in Polish and I don’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. A friend sent me a graph that shows frustration and plateau in level B1, which is where I am. There’s a kind of opaqueness to Polish that I never felt with other foreign languages that I was learning, which manifests itself for me in not realizing that people are speaking to me when they are speaking in Polish unless we are actively engaged in a conversation. It’s akin to how I can read a book in Hebrew, which I speak fluently, but I have to properly concentrate. Like I have to say, “Hello, book, I am reading you now. Please unveil your secrets to me.” A book in Hebrew is not like one in Latin letters where key words will jump out at me and wave, “Hello! Read me!” Even my name does not do me that courtesy on a full page of typed Hebrew text.

A fun thing I am doing is reading the transcript of an interview my mom gave in Polish to Brama Grodzka in 2005. This is great because 1). I know the topic very well so I can understand probably 80%. 2). I am interested in the topic and 3). The text contains vocabulary that is useful to me.

I don’t usually find that New Year’s resolutions work, but if they did I would make one to rededicate myself to speaking Polish. I do love my Polish teacher and having three private lessons per week is a great thing.

For those who don’t know any Polish: Don’t those words look crazy?! Polish scrabble must have tons of Ws, Ys and Zs.

Family Discoveries and Anti-Semitism

Today I found (well, my friend a genealogist who helped me, found) my oldest known relative’s death record. Lejb. He was born in 1800 in Parczew and died in 1874 in Kock (pronounced Kotsk). He and his wife Chaja Gryna were grain traders. Chaja Gryna’s father was named Pejsach. Pejsach was likely born in the 1700s so I guess Lejb is not really my oldest known relative but he’s the oldest whose birthdate I know. I am sure all these people were religious Jews.

I met another relative yesterday and she’s really great. She is 20 years younger than me but on the same level of the genealogical tree. I still cannot get over the fact that I have living relatives in Poland. They are descended from my grandmother’s first cousin who survived the War. She was saved, like my mother, by non-Jewish Poles. I am excited to meet more members of the family. I went to ZIH (the Jewish Historical Institute) to tell Anna P. that I had actually met the people she had told me about. When I was telling her about meeting living relatives in Poland I felt myself getting emotional. She asked if she could hug me. It’s such a mitzvah what the people at ZIH do. Not only the people at ZIH but all the people who do genealogy for people and help them find connections to this land that is so often dismissed as a cemetery, a place of so much pain that it is not worthy even of setting foot on. But if it is that, if it is only a place of loss and death and pain (and my experience teaches me that it is so much more) wouldn’t that compel the opposite response? Wouldn’t we want to visit? To pay homage? But I am forgetting that this is not a logical endeavor. When pain is involved, when the emotions and the heart are involved all bets are off. It makes sense that a human being would not want to feel all that pain again and again. And it makes sense that people would need to blame someone for their pain. I guess that’s where any form of hatred comes from ultimately—some sort of pain.

A few months ago I heard an anti-Semite speak in a Polish church in Boston and the crowd was very much on her side. I had never been in such a hostile environment. There were even two priests in the audience. I could feel where the anger was coming from. My impression was (the event was in Polish) that there was a feeling among the audience members that their victimhood had not gotten enough air time, that the Jews had gotten too much of the spotlight and now they wanted their due, and it seemed the only way to do that was to diminish what had happened to the Jews.

Somehow this post has gone from meeting family in Poland to Polish anti-Semitism. My relative told me that it was never a problem being a Jew in Poland. His parents (both Jewish) had considered leaving in 1948 but not, interestingly, in 1968 during the so-called anti-Zionist purge. But when I asked if there was anti-Semitism in Poland both he and his wife answered, “Of course!” I am curious to explore this topic further. I have found the most interesting parts of the conversations I have been filming as part of my fellowship here, is when I ask people about their childhoods and what they did or did not hear about Jews and anti-Semitism. It varies greatly.

The Internet, at least, thinks I know Polish

Since I am in Poland, when I do a Google search the results come up in Polish. Just today when I write an email I have started getting English words underlined as if they are spelled wrong like used to happen with other languages. Seems that Gmail is expecting Polish or something.

Thanksgiving

It’s Thanksgiving, but here in Poland it’s just a normal day. I would not even realize it but I go on Facebook and everyone is saying what they are grateful for, and I listen to Boston Public Radio and they are not broadcasting live today or tomorrow.

Today is also 55 years since the JFK assassination. I asked my Polish friend and visionary preserver/guardian/keeper/protector (am trying to figure out the right word) of Jewish memory what his first historical memory was (he was born in the 1950s) and he said the JFK assassination. He said his second was the moon landing. Even more than the expulsion of the Jews from Poland in 1968. This is something I was recently discussing with my older son. Mine is Robert Kennedy’s assassination. His was Clinton’s second election.

I lived in Israel for eleven years (twelve really, but eleven in a row) and Thanksgiving was usually just another day there as well though I think maybe once or twice the expats did something.

So what am I thankful for? Of course my wonderful children. R. with his glorious sense of humor and his boundless generosity of spirit. He is the world’s best hugger. A great writer, a great creator of metaphors. A sensitive and uproariously funny soul. He does not just take things as they are but asks why.

L. who always tries to help people, who, when he was little and someone left a jacket at a soccer game wouldn’t rest until we got it back to the person. He has the patience of a saint and always explains every little technology thing to me and to other family members. He does great accents. Being with him and R. is like being in a constant improv show. L. knows so much about so much: wine, coffee, credit cards, cell phones, plane tickets. And if he doesn’t know he’ll find out. And he’s a sharp dresser. And they both have quirky, unique takes on the world. Oh, and both those boys can cook!

I am grateful for K. and M., the loving girlfriends of R. and L. and I am grateful that the four of them get along so well. I am grateful for Melvin and Linus and that R. and K. gave them a home.

I am grateful for my brother and my parents and for all the generations who came before. I am sorry that so many were cut short too early but I am honored to be here to represent you.

I am grateful and thankful for my friends in the States and elsewhere and particularly right now in Poland, particularly my friends here who are doing the work of Jewish remembrance, who are driven to do it. In talking with my friend today he said that so much of what he does and what drives him cannot be explained by logic or rationally. It isn’t rational. And I think that’s the beauty in so much of this work. It requires a leap of faith. It has an element of love or magic or faith. If that scares you or makes you roll your eyes then maybe some what I love won’t resonate with you. But I am so thankful to those willing to take that leap of faith. My friend P., after coming on one of my Bridge To Poland trips in 2017 said one of her big take aways was the power of art to convey things that words cannot. I just listened (today) to an interview that I did with Brama Grodzka back in 2008. I only had a vague recollection of even doing the interview but in it I said that I could not yet put into words all that I had experienced in Lublin. It was too big and too deep. I said that I was not sure I would ever be able to put it into words, perhaps I would in the future, but for now I did not have the words, I just knew that returning to the city of my ancestors was a powerful experience.

In these months, in Lublin, surrounded by people dedicated to remembering those whose voices were silenced too early, and surrounded by traces and intangible memory of my forebears, I will try to find the words as I work on my book about my experience discovering Poland and discovering the beauty and the magic that was waiting here for me.

Happy Thanksgiving.

No Expats, Everyone's My Teacher, Buses and Poles Speaking English

I realized that for the first time I am living abroad without an expat community, which is pretty cool. Every other time, whether I was studying (Spain, France, Italy, Israel, Poland) or living my life (Spain and Israel) there were always expats around. This time in Poland I am flying solo and happy to be doing it. Thanks again to the Fellowship Committee at Wellesley College for awarding me the Mary Elvira Stevens Traveling Fellowship and providing me with this fabulous opportunity.

Being immersed in Polish society means more opportunities to practice my Polish. Everyone here is my Polish teacher, whether a close friend or someone in a shop. If I grit my teeth and plunge in with my less-than-perfect Polish I have the opportunity to learn something. Many are gracious, willing teachers. Some are not. Some get that I really want to speak in Polish, as hard as that is at times (And I really appreciate those that wait patiently while I look for the right words). Some don’t have the patience and switch to English.. Some don’t have the patience or the English. Yesterday I went to the PLAY store. PLAY is the company that I have my phone plan with. So I went into the store to ask some questions (why was I using so much cellular data, why did some texts go through while others did not, etc…). First the woman said she did not understand what the phone said because it was in English. Then I wanted to ask her a question about the SMSs and why only some went through. I know that the iPhone messages are blue and the others green and it was hard for me to explain in Polish without just saying, “the blue ones and the green ones.” She started rolling her eyes and practically mimicking me and said she did not understand. I said, “I don’t think Pani (formal form in Polish) wants to understand.” To my American ear it’s so funny that you can use this formal form to a young woman who is half your age and be complaining, but still be technically polite!

My real teacher, Magda, is great. Turns out she was my teacher 11 years ago when I was here and through happenstance we reconnected. She is a great teacher. I take the bus a half hour to her place. Two of the stops on the way to her place are Sympatyczna and Fantastyczna—nice, or likeable and fantastic! A lot of people got off at Fantastic tonight. I am proud of having mastered public transportation, as that is not my forté. I went to a kiosk buy the bus tickets and bought 20 at one fell swoop (this was before I learned there’s an app that allows you to buy the tickets online), and the woman at the store was incredulous: “You want 20?!” I guess no one had ever bought 20 tickets at once before, though I don’t know why. If you use paper tickets why would you want to have to buy them each time?

I am doing an Polish-English exchange with a woman at Brama Grodzka and also doing English conversation with a friend of mine. I am also paying attention to the kind of mistakes Poles make in English*. Here are some common ones:

Pronouncing letters that should not be pronounced. Examples: AnsWer; BomBing; CasTle.

Saying “we” when it should be “I” if the speaker did something with one other person. Let’s say Adam went to the movies with Dorota. Instead of saying, “I went to the movies with Dorota,” Adam will say, “We went to the movies with Dorota.” I imagine I make the opposite mistake in Polish!

Overuse of the present progressive/using it where the simple present should be used, like when there is a habitual actual. Instead of, “Some people visit Auschwitz every year,” they say, “Some people are visiting Auschwitz every year.”

Academical for Academic. (Not recognizing that Academic is both a noun and an adjective). And Economical for Economic.

If you are still here you are a word nerd just like me!!! Yay us!

*Please note that whatever mistakes they make, all my friends’ English is way better than my Polish, though I am working to close the gap!

Poland Today. Line 23.

The same bus goes to Ikea and to Majdanek.

Trains, B&Bs and relatives

I took a train from Warsaw to Lublin yesterday. It took 4 hours and 40 minutes instead of 3 hours. They are still working on the tracks but also there was an accident. Rumor had it that there was a body on the track. I don’t know if that was true. They did come on board and give all of us a bottle of water. When I saw that I said to the other woman in my cabin, “Uh oh, it’s never a good sign when they start passing out supplies.” “At least it’s just water,” she said, “Not food.” She was a biologist from Kraków on her way to a 4 hour sea shanty concert in Polish in Lublin! And she was reading a text book about sailing.

I was the only one in my Kraków B&B the other night! Weird but kindof cool too.

I love the B&B I stay in in Warsaw. Each room is different, mostly named for Polish painters. I met a couple from Colombia at breakfast and we were having a nice conversation when the wife said the B&B reminded her of a ghetto (we were speaking Spanish). I said that for me a ghetto means a place that Jews were forced to live during WWII. She corrected herself, “I meant a kibbutz.” (Oh you know, one of those places Jews live in groups!).

I met my newly discovered relative Mietek the other day. (thanks to Anna at the Jewish Historical Institute for finding out about him). He lives in Katowice but came to Kraków to meet me. His mother was my grandmother’s first cousin. She, like my mother and my aunt and grandmother were saved by non-Jewish Poles. It’s so cool to discover these new relatives who are very warm and friendly. Both of Mietek’s parents were Jewish and he has always identified as Jewish. He said it has never been a problem everyone at work knows he is Jewish. But when I asked about Polish anti-Semitism both he and his wife said of course there is anti-Semitism in Poland. I look forward to meeting other members of the family.

Parczew, where my grandfather’s brother and sister were born, from the train window.

Bathroom door (from the inside) in the B&B.

Bathroom at the B&B.

Bathroom at the B&B.